According to LGBTQ legend it was Marsha P. Johnson, a black transgender woman, who threw the first brick at the Stonewall Inn 50 years ago, sparking the modern gay liberation movement.

Whether her act of rebellion was truly the first in the rioting is debatable, although she was “almost indubitably among the first to be violent,” writes David Carter in “Stonewall,” his 2004 book about the police raid on a New York gay bar that became a historic moment.

What is certain about Johnson’s role, at least for today’s transgender community, is that the stone she cast packed the most thunder.

Johnson, along with a fellow transgender woman Sylvia Rivera, who was of Puerto Rican and Venezuelan heritage, became inspirational leaders of the movement born in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, when lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other queer people fought back against harassment.

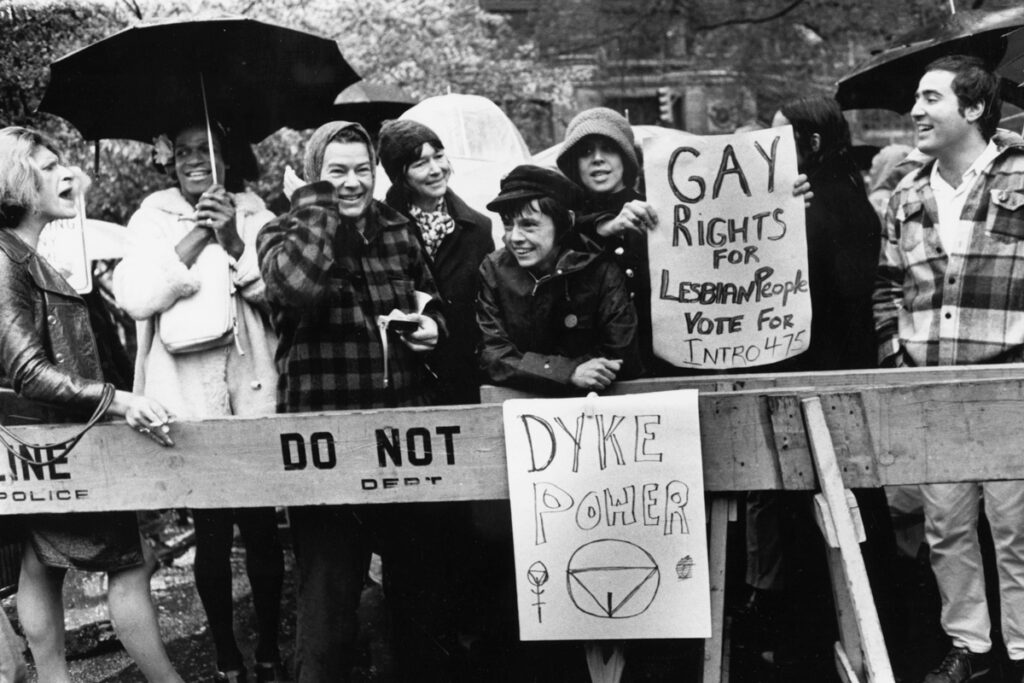

The months after Stonewall were a time of LGBTQ unity that would not last long.

Gay men, mostly white, assumed leadership and ostracized trans women like Johnson and Rivera in the name of respectability, according to people involved in the movement at the time.

As the 50th anniversary of Stonewall approaches, Johnson and Rivera are receiving a belated measure of recognition in death that coincides with a growing awareness of transgender rights.

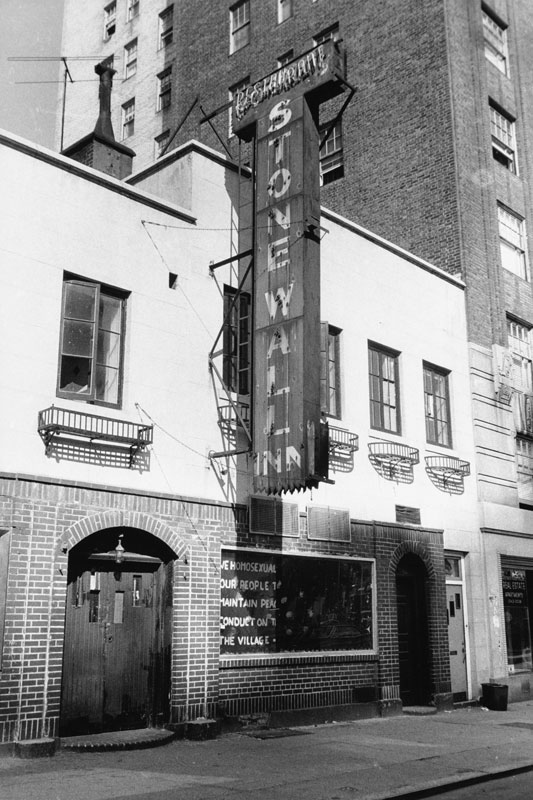

New York City announced last month it would build a memorial to Johnson and Rivera near the Stonewall Inn, the Greenwich Village bar whose name has become synonymous with LGBTQ rights.

“It is certainly sad that their memories were not only forgotten but desecrated in many instances, and now they are at least back in the conversation,” said Andrea Jenkins, a black transgender woman on the Minneapolis city council. “I’m still not sure if they are getting the absolute credit they deserve.”

The announcement was made as New York prepares to welcome 4 million visitors for World Pride 50 years after Stonewall. The annual parade — the legacy of a march organized by Johnson, Rivera and others on the uprising’s first anniversary — is set for June 30.

Last week, the New York Police Department apologized for the first time for the raid.

Transgender advocates revere Johnson and Rivera for becoming the public faces of the most marginalized among LGBTQ people, for standing up to police harassment, and for insisting on respect.

“They were so remarkably brave and had such an immediate and long-term impact,” said Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, the largest U.S. trans advocacy group.

The two have been memorialized in a 2017 documentary “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson.” Their names grace the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, a New York advocacy providing legal services for trans people, and the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, which promotes transgender human rights.

‘A MAGICAL YEAR’

In 1969, police raids on gay bars were routine, although Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine’s infamous raid on the Stonewall was mostly aimed at its Mafia owners, according to Carter’s book. It was a time when LGBTQ people were treated like criminals and generally acquiesced to harassment.

The scene at the Stonewall Inn was different.

An angry crowd gathered outside and began throwing coins, beer cans and bricks at the police, who barricaded themselves inside. The weaponry grew more menacing with the use of fuel-filled bottles and a parking meter used as a battering ram. It was an act of resistance that still reverberates.

Soon after the rioting, Johnson and Rivera became active in the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), the first known pro-transgender group in the United States, providing shelter for the abandoned and homeless.

But before long, the mainstream gay rights leaders dominated by white men lost patience with the political radicals of GLF, said Mark Segal, 68, a gay rights leader and GLF veteran who was in the Stonewall that night. Within a year, the Gay Activists Alliance formed, insisting on a more respectable image.

“For that first whole, magical year, we were a united community across the board,” Segal said. “And that all went away once the Gay Activists Alliance was formed.”

By the time of the fourth anniversary parade, organizers banned “drag queens,” so Johnson and Rivera marched in front of the parade banner, outside the official event. Rivera was booed when she took the stage in the rally at Washington Square Park.

Rivera was known for being combative, according to people who knew her. She often chastised gay activists as willing to fight for their own rights but not for trans women who were beaten and raped in jail.

Johnson was admired for her generosity and compassion. With her magnetic smile and over-the-top fashion sense, Johnson captured the eye of artist Andy Warhol, whose 1975 portrait forms part of his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series.

“For that first whole, magical year, we were a united community across the board. And that all went away once the Gay Activists Alliance was formed.”

MARK SEGAL

Gay rights leader

“Marsha P. Johnson was a living saint,” said Randy Wicker, 81, a longtime gay activist who was roommates with both women at different times.

Neither referred to herself very often as “transgender,” if at all, as the term was not yet common. Instead, terms such as “transvestite,” “drag queen” and “transsexual” were used interchangeably. But they lived almost exclusively as women, and transgender people today consider them two of their own.

Johnson died at age 46 under mysterious circumstances, her body pulled from the Hudson River in 1992. Rivera, who had been homeless at times and suffered from addiction, died in 2002 of liver cancer at age 50.

In the years since their deaths, a new understanding of gender identity has pushed its way into the mainstream. That has brought about a measure of reconciliation between transgender women and gay men, who have become a powerful coalition influencing policy on LGBTQ rights and fighting discrimination.

Even so, some transgender women of color say they still feel the sting of those old wounds, making them less inclined to celebrate the Stonewall anniversary. The work began by Johnson and Rivera is far from complete, they say.

“There is still a divide,” said LaLa Zannell, a New York-based transgender rights activist. “We moved forward 50 years and where has the T really evolved? We’re still homeless. We still can’t get jobs. We’re still marginalized.”